In conversation with Katie Schorr

I think I’ve always been interested in [art]. Probably one of the biggest reasons was that I’m very dyslexic. As a child, I was always at the bottom of the class and they told my mother I was stupid, she constantly said, “This girl isn’t stupid.” And in order to build me up, she used to give me art materials. I used to draw and paint and fiddle about in my Dad’s workshop and I felt good doing it. After completing school I went to an art school and did a foundation year like you do here, this was in Durban, South Africa and got into printmaking rather than painting because it was a fine art, but the emphasis was on drawing. I love drawing, and the physical-ness of printmaking.

I think I probably would have [become an artist] anyway, but, yeah, [my mother] did encourage me. And I guess my father did too. They knew I was comfortable painting, drawing and making things. Probably they did at school too. I’m sure I wasn’t that best drawer in the class, but I enjoyed doing it.

They say that dyslexics have got a much better spatial sense. I don’t know about that. I’m not a good reader, I read very slowly so I am very selective about what I read, I listen to audiotapes quite a bit. But I do think that the lasting effect is the feeling of inadequacy; I have always felt inadequate. And perhaps only over the last two years, I’ve come to terms with that. I don’t really care anymore; that’s how it is. Probably as you get older, you just get wiser and you just say, “Well, some people may have squiggly ears and other people can’t read.”

I don’t think I was limited by my background, but I think it’s taken me a long time to really get over the guilt of being South African and having grown up there and not really being part of it. I don’t know what effect it’s had on my work. I don’t feel totally part of it when I go back because as I wasn’t there during the changes. Everything’s changed. When I left South Africa, there were still benches for white people and benches for black people and black people didn’t get on the same bus as me. It’s completely different; it’s a different country- a better country.

I did three years of printmaking and then came to England where I studied printmaking at Croydon School of Art, just outside London. It was post-graduate and all seven of us on the course came from different parts of the world and that, for me, as a South African, was very exciting because in South Africa you didn’t really have contact with people from abroad.

But it was also a difficult year, in South Africa we had been taught to look to Europe and America for our influences, there was heavy censorship in South Africa. This was 1979, a very bad time politically in South Africa. My head of department would say, “Well, why are you drawing a chair when you, of all people, have got the most to say? You come from a country that’s war-torn, that’s full of ugly politics, apartheid, why aren’t you talking about these things?” And the truth was, I didn’t know about them. I knew it was there, but we were so cut off from the reality in South Africa that it wasn’t really part of my life. It sounds awful, but it wasn’t.

I began to realise that I had lived in South Africa for seventeen years and hadn’t been part of it and I was being judged and accused. So I went back, I worked for a small left-wing group where I was employed to illustrate a self-help book and we went out into rural areas where we helped to set up a candle factory and did demonstrations on various alternative technology projects. But I found it was very difficult as an artist to be there. It was dangerous to express your thoughts and I wasn’t prepared to be locked up for it and painting ‘pretty pictures’ seemed to be too dishonest.

So again I left South Africa, I came back to England where I had met my husband Korky the previous year. He’s also an artist, a children’s book illustrator. He’s from Zimbabwe and grew up in South Africa. He had been at the same art school as I was in South Africa, only some years before me. He had studied animation in California the same year that I was studying fine art here [in Britain]. We had a lot in common. We’d both gone through a sort of awakening of South Africa. His was different in that he had had to do military service in South Africa and active service in Angola, which wasn’t much fun. So he definitely had run from South Africa, not to return. I don’t know that I was ever as sure as he’s been about staying here. And probably I would, even now, make a go of going back again, but he wouldn’t consider it.

When you’re eighteen, love means passion and excitement. I guess it’s pretty clear when you’re that age, what [love] is-being with someone who understands you. When you’re younger than that, really young, I don’t suppose it’s even a question because you just know that it’s all around you. It might not be for a lot of people, but it was for me. After you’ve been with someone for 20 years it’s a different sort of love. [Love] just gets more complicated as you get older because you realise there are many strands of it. The love for your children is different to the love you have for your friends or husband.

Again, I left [South Africa] and came here in 1981. And I joined up with a print workshop and did a little bit of printmaking. I got into children’s book illustration because that seemed the best way of making some money out of my work. I did a number of children’s books and I did quite a lot of illustration work for magazines and then got into book covers. I did about thirty of forty book covers all together, for novels, which was interesting. I had to get the gut of what the book was about, and then find an image for it. I was seldom given a tight brief. It was very fulfilling work and I was really aware of the responsibility. An author had spent years working on a novel and my illustration was going onto the front cover.

And I did a book which won the Booker prize. [The book was Hotel Du Lac by Anita Brookner.] On the strength of that I was asked to illustrate many titles including series of Mary Wesley books, there were about thirteen all together.

We bought a house in Greece around this time as we craved the sunshine and we loved the lifestyle. At this point, Korky was working for a Greek publisher, so we were spending a lot of time there. I was doing a lot of painting, which I exhibited in London. The editor of Jonathan Cape saw the exhibition and commissioned me to do ‘Hotel du Lac’. I did the cover not knowing that Anita Brookner was an eighteenth century watercolour specialist, I would have frozen had I known that before. When she won [the Booker prize] my phone didn’t stop ringing, it was as though I had just won. Publishers wanted me to do their covers, I suppose my work was fresh and different at the time. So book cover work really took off from there.

It was luck that she had come to the exhibition and was looking for someone to do the cover. I was in the right place at the right time. I probably would have got into the fine art world earlier had that not happened because I was wanting to exhibit my work and I was doing a lot of painting. I would have approached galleries, however it was very good for me, I had my 2 children around this time and I wasn’t able to do a lot of work. Even a couple of books a year were still keeping my work in the public eye.

I did a lot of work related to children, paper mache projects for books and children’s illustrations, and all the time doing a bit of painting, but not exhibiting it. And then when my son was two, I joined the Oxford Printmakers and printmaking took over again. The printmaker’s was set up about twenty years ago by a group of printmakers as a co-operative and it’s still going. It’s got fantastic equipment. They run workshops; they’ve got facility to do silk screening and etching. And they have membership so you join as a full-time member and then they give you a key and you just go when you want to.

It’s total commitment to children; they’re so vulnerable. And you want to protect them and do the best for them. It’s a very different sort of love. And it’s even a different love between each child.

As a mother, your own thing comes at the bottom of the pile. That doesn’t mean they’re not important, they just have to wait. There was probably a period of about ten years when I didn’t do my own expressive fine art work. When I got back to it, after having kids, my work came out in a completely different way, and quite an exciting, refreshing, totally unexpected way. And that can only have been because I had taken time out and thrown myself into the family and children. I guess my work is very playful because of it.

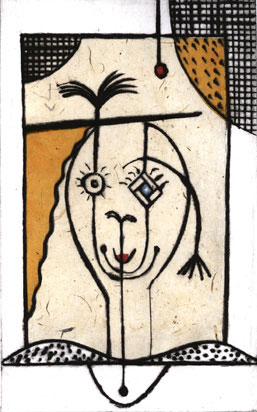

I don’t know that it’s one idea that comes into my head when I start working. Sometimes it is; sometimes it really is. I know that in the last year I’ve done some work that was directly related to the Iraq War. And that started because I painted a dove on a piece of sheet and I hung it outside the house. And when I drove past one day, I thought; it’s completely wrong. That dove is too influenced by the West; it’s too Picasso-ish; it’s too blue; it’s too gentle; it’s just not right. It doesn’t portray any of the anger I feel. And it doesn’t portray the place- Iraq.

So I started to research art from Iraq. I found some manuscripts that were done in Baghdad in the 12th century. And they were just so rich and so much a part of that world. These manuscripts were illustrating fables called ‘Kallila wa Dimna’ all depicting vices of man through animals. The stories were so relevant and I realised that my dove mustn’t be blue; it had to be red; it had to do with Iraq.

I translated my dove into this rather aggressive bullet-like red Iraqi bird. This led on to a whole series of prints I did, six or seven of them, all to do with these fables. So each of them has got a story that was absolutely relevant to the war. But my pictures don’t always come like that.

I think what happens is you just collect ideas. People always ask me how long it takes to make a picture; well, it takes forty-nine years. I’m forty-nine years old. I don’t know where it comes from. I think you collect things and you make a little database.

Sometimes I haven’t got an idea of what you want to do, so I just fiddle around with old ideas from sketch books or rough drawings then something triggers off a sort of a conversation.

In printmaking, I’m working on a lot of plates; some of the pictures take four or five plates. And some of the plates are very abstract because maybe they’re just a blue plate or they’re just a yellow plate. Sometimes if I’m really in a lull and I don’t know what to do, I print up one plate, perhaps turn it upside down and there’s something new in there. There’s something to go from; there’s an image.

I remember one of my teachers at art school in South Africa, saying “a blank piece of paper hasn’t any tension until you put one mark onto the paper, then you’ve got tension between the edges of the paper and the mark. and your eye starts moving. If you then put in another mark you’re getting more tension, and more movement. Soon you have a whole conversation going on.” So, if I’m stuck I try to work in this way.

About six or seven years ago, I formed a group with three other women. We are all printmakers, we rent space at fairs and exhibitions where we exhibit together about four or five times a year, it works really well. Our work is very different so we don’t feel in the slightest bit competitive. It’s a very good way of selling. We share all the costs and the time. We’ve brought out brochures and have a Webster and we try to present ourselves like a gallery. We take people on commission as well, sometimes. But selling your own work is very different from selling other people’s work.

I think when you’re in the studio and you’re working on a picture the last thing you’re thinking about is selling it.

Editioning is part of the printmaking process. I usually make around twenty of each print. I sell them through galleries as well as directly myself or at fairs.

Artweeks [in Oxford] is a wonderful way to exhibit and sell my work. I’m the co-ordinator of this area and I realised after the second year that I’d done it that we were all opening our houses and mostly we were looking at each other’s stuff. The public didn’t really know what it was about. So we published our own separate guide with a map so that people knew if they came to this area, they could see a number of artists in a limited time.

We also decided to do a street festival, which is now in its fourth year. We had a few bands the first year, but now we’ve managed to get a bit of sponsorship and someone to run the festival. It’s still on a shoestring. But this year it was on a much greater scale and it has made people aware of Artweeks. It’s also good to be involved with the community. It now feels like it’s something in Summertown’s calendar and people look forward to it and support us. But I think the interesting thing about Art Week too is that exhibitors are professional and some people aren’t, everybody is on a level playing field. It’s a very good thing.

Most teachers would say that you could teach [children] about any subject through art and I believe that there are techniques that can and should be taught. You can also be taught to look at things in a different way. As children get older, they get more inhibited. Unfortunately secondary schools don’t take art as a serious subject. Yet everything around us has to be designed and made, and fine art is just as valid an expressive art as literature, theatre, music etc.

The art world at the moment is so confused that it’s very difficult for people to make an individual judgement. There’re a lot of reviews on music and theatre and drama, but generally the art critics are pretty cynical. There just seems to be a feeling at the moment that artists are not taken seriously.

I started [doing Art Weeks] six years ago and we’d just moved to this house. I did know about [Art Weeks] before, but it wasn’t possible before to do it. And [my husband and I] both exhibited here which was good, by then; Korky was already quite well known. We had hundreds of children coming. The first day we opened, there was queue all the way down the road because he hadn’t ever done that before and people wanted to come to the house.

I take opportunities as they come. I don’t think I’m scared to try new things, sometimes you make mistakes but you learn from them too.

When frightening things happen, you’ve still got to deal with them. There’s a way through most things and sometimes the outcome is not what you expected.

Sometimes you make decision in your life that change things completely. The day that I decided to come and study here from South Africa was momentous, but at the time I didn’t think I was leaving my home and country forever. Maybe today I’ll make a decision that’ll change the rest of my life; I don’t know. I just don’t know.

I’d like to develop or acquire knowledge and skills in everything! Because the more skills you have, the more diverse your expression can be. If I knew about sculpture and casting and bronze, fantastic, then I could move into that. This idea that artists don’t need to draw anymore is complete rubbish. The more techniques you have at your disposal, the more you can express whatever it is you want to say.

I don’t think I’d shy away from trying anything if the opportunity came along. I was asked two years ago to do two large stained glass windows for a school. It would be impossible to design a stained glass window unless I knew the medium; I learnt how to do it and that has led onto other projects. I’d love to do sculpture. That’s a whole new discipline; it’d take years to master it. I still want to learn it.

I don’t know that I’m conscious of [fear or loneliness] in my work. I’m sure if you’re feeling upbeat, your pictures are upbeat. If you’re feeling dark and gloomy, I suppose they would be too.

Art prevents me from being lonely. I always think that making a picture is very much like a conversation because you set up an idea and then it tells you what to do and you add to it, like a discussion or argument that has to be resolved. How can I be lonely? I’m too busy!

I haven’t really got a home. South Africa isn’t really home because I’ve spent too long away, although my dad’s still there, my brothers are still there, and I still have lots of friends. When I go back, to familiar sounds and smells and colours, I get that lovely, warm, gutty feeling of going home, perhaps that’s nostalgic stuff. England, no I don’t think this is home either. We’ve been here long enough; it should be and our children are English. But I don’t think I’ve become anglicised. And Greece? I speak the language and we live in a small village and we socialise a lot with the people there, but I’m foreign there too. If you ask me where I wanted to die? I don’t know. I probably wouldn’t like to die in any of those places. I’m sure more and more people feel homeless. Maybe home is where you feel the most connected to a nest and that’s probably when you’re a baby, when you’re a child.

Life should never be complete. You don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow. I’d like to travel a bit more. I’d like to spend more time with my father and brothers and sister and I’d like to have more time to paint, which I will have when my children have grown up and left home. But I don’t look forward to that, I would miss them. So I’ll just go on like I am and just try and fit in whatever I can. I don’t think I want to be any more complete.

June 2004